Sermon: Yom Kippur

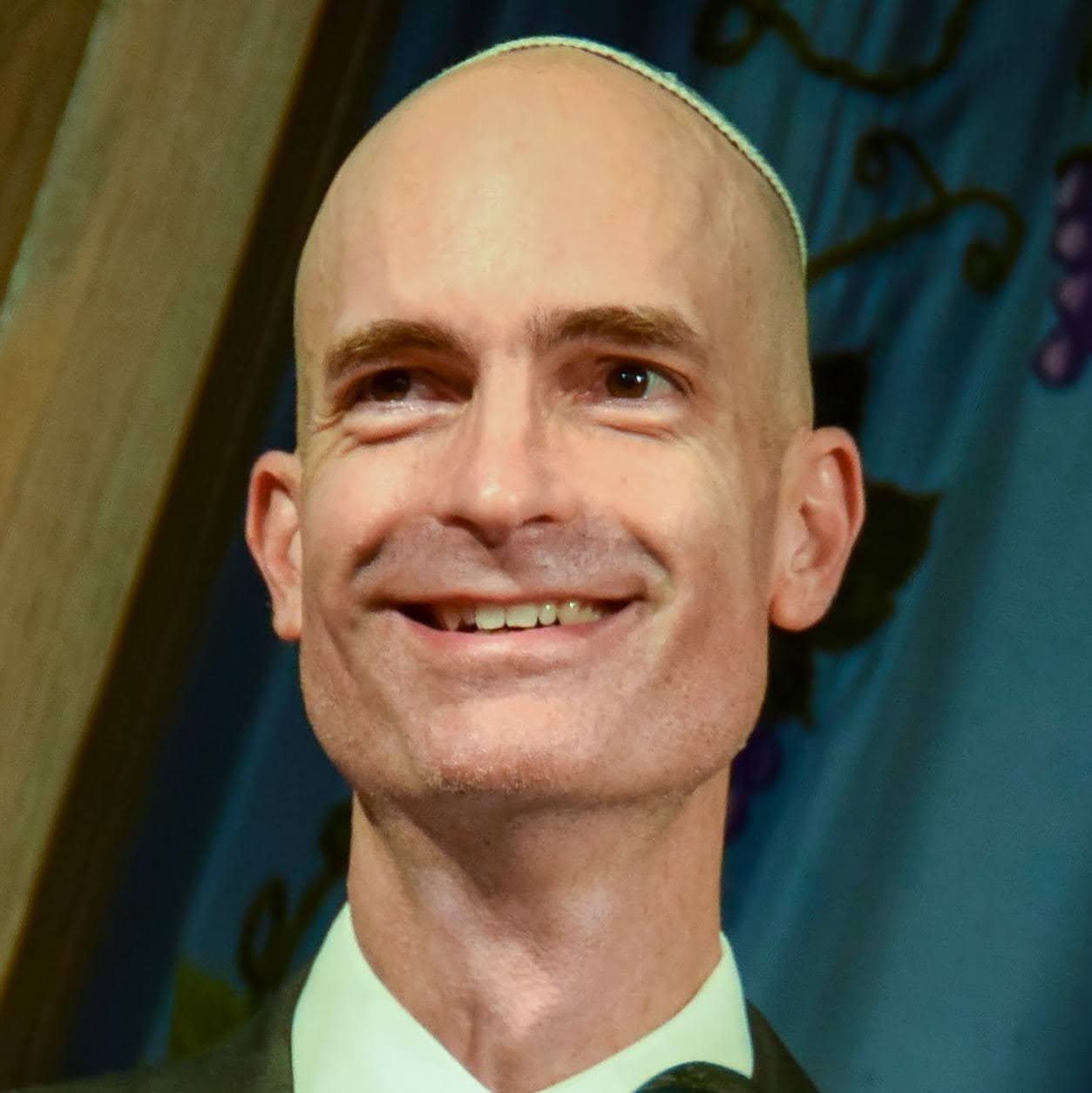

This sermon, “The Connected Critic” by Rabbi Justus Baird was delivered at Congregation Shomrei Emunah in Montclair, N.J. on Yom Kippur 5786 (Oct 2, 2025).

I want to start with a story that took place 120 years ago, in 1905: the same year that a small group of Jews in Montclair and Bloomfield came together to start what would become our synagogue – Shomrei Emunah.

In November of that year, Rabbi Stephen Wise received an invitation he had been anticipating for many years: the chance to become senior rabbi of Temple Emanu-El in New York…arguably the premier synagogue in America at the time – no shade intended on the haimish gathering that was happening here at the future Shomrei. Rabbi Wise, who was 31 at the time, had already developed a well-known reputation as a great orator, an outspoken voice for justice, and an ardent Zionist, even though that view was then very unpopular in the Reform movement that he belonged to.

Rabbi Wise travelled to NYC all the way from Oregon to meet with the Emanu-El trustees and discuss their invitation. When he sat down for the interview, Rabbi Wise made seven requests:

1. His election must be unanimous by the trustees and the congregation, for a term of three to five years; and if things went well, he would stay indefinitely

2. He would preach three times a month, addressing his messages both to Jews and to non-Jews;

3. He would invite guest preachers – not limited to other rabbis;

4. He would participate in prayer services, not leaving that ritual task only to a reader;

5. He would require a secretary

6. At some point in the future, he would launch a downtown satellite of the synagogue to serve the needs of the immigrant Jewish masses there;

Although a few trustees raised their eyebrows at some of these requests, they all agreed. Then came Rabbi Wise’ seventh request:

7. “the pulpit must be free while I preach therein”

Immediately Louis Marshall objected. (Louis Marshall, you may know, was a prominent lawyer who would later become a director of the NAACP and part of the legal team that represented Leo Frank.) Marshall said: “Dr. Wise, I must say to you at once that such a condition cannot be complied with; the pulpit of Emanu-El has always been and is subject to and under the control of the board of trustees.”

“If that be true, gentlemen,” Rabbi Wise shot back, “there is nothing more to say.”

The trustees conferred, and then pushed Rabbi Wise to explain what he meant by a “free pulpit.” Here is what Stephen Wise told them:

Mr. Moses, if it be true, as I have heard it rumored, that your nephew, Mr. Herman, is to be a Tammany Hall candidate for a Supreme Court judgeship, I would, if I were Emanu-El’s rabbi, oppose his candidacy in and out of my pulpit. Mr. Guggenheim, as a member of the Child Labor Commission of the State of Oregon, I must say to you that if it ever came to be known that children were being employed in your mines, I would cry out against such wrong. Mr. Marshall, the press stated that you and your firm are to be counsel for Mr. Hyde of the Equitable Life Assurance Society. That may or may not be true, but knowing that Charles Evans Hughes’s investigation of insurance companies in New York has been a very great service, I would in and out of my pulpit speak in condemnation of the crimes committed by the insurance thieves.”

To Rabbi Stephen Wise, a “free pulpit” meant that the rabbi was free to call out moral concerns wherever he saw them, especially when they emerged from his own community.

Perhaps it won’t surprise you that Stephen Wise turned down the invitation to become senior rabbi of Emanu-El. He was so committed to the idea of a free pulpit that, a couple years later, he founded what he called the Free Synagogue in NY, now called Stephen Wise Free Synagogue.

Let me be clear: I did NOT open with this story on Yom Kippur as some kind of subtle but public warning to Shomrei’s board members about any upcoming contract negotiations with my wife, your rabbi.

Rather, I opened with this story to introduce the idea of critiquing in public, more specifically, the role of a social critic.

During the high holy days, and especially YK, we often reflect on our personal wrongdoings. What do I want to improve on next year? Who do I need to apologize to? Which of my relationships need extra attention?

But the focus of YK is at least as much on our collective behavior, as it is about our individual behavior. Consider the Ashamnu, a collective confession. We don’t say, ashamti, bagadti, I am culpable, I have been unfaithful. We say AshamNU, bagadNU, we are culpable, we have been unfaithful. Or consider the Avodah service later this afternoon, which begins with the high priest acknowledging his personal failures, then the failures of his household, and climaxes with the High Priest asking forgiveness of the collective, the people Israel.

The high holy days are prime time for reflecting on our collective behavior, and how we can improve as a society. But how, exactly, do we improve as a society?

Surely one key ingredient in any process of improving our society is social criticism. We need people who reflect on how we’re doing at the societal level, who point out when we are collectively falling short. The voice of the social critic can take many forms: clergy, artists, musicians, writers, social activists.

But if we’re honest with ourselves, I think almost all of us imagine ourselves as a social critic. We look around, at our town and our state, the Jewish community, our country, at other countries, especially Israel, and we judge. We critique. We ask incredulously, did you see the news? Can you believe what is going on? Most of us don’t broadcast our critique beyond our coffee chats, kiddush conversations, or social media feeds. But I would argue that even those semi-private conversations matter – they are the places we test out our thinking, the places we begin to form collective opinions.

Let me try to persuade you that the stakes of social critique are very high.

In the Talmud, Tractate Shabbat,[1] Rav Amram taught: Jerusalem was destroyed only because the people did not criticize one another. In his explanation, commenting on a verse from Lamentations,[2] he suggested that the Jews of that generation were like deer whose heads faced each others’ tails, a generation did not criticize one another.

Now you may be thinking: Rav Amram must be meshugah. Could there ever been a generation of Jews who did not criticize each other? But let’s focus on his core message: Jewish society fails when Jews do not take responsibility for critiquing each other.

In another rabbinic passage,[3] the rabbis struggle with the practice of rebuke, tochecha. What happens, they say, if someone rebukes someone else four, maybe five times and that person doesn’t change? Faced with the reality that people don’t always respond to rebuke, Rabbi Tarfon said, “In this generation there is no one capable of rebuking.” Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah said: “In this generation there is no one capable of receiving rebuke.” Rabbi Akiva said: “In this generation there is no one who knows how rebuke ought to be worded.”

I hear in these words a frustrated lament: we know we’re supposed to rebuke and critique, but our rebukes aren’t working! We don’t seem to know how to critique effectively!

In our generation, we also have a problem with critique. The phrase “everyone’s a critic” provides a good summary. Consider movie critics: anyone remember Siskel and Ebert? [Make thumbs gesture] But today, all we have is Rotten Tomatoes and IMDB. Each review we post of a movie or restaurant or product or news headline: we have indeed, all become critics.

Nevertheless, with all this critique, society does not seem to be responding. The rabbi’s claim that “there is no one who understands how rebuke and critique ought to be worded” rings true for our generation too.

As a possible way out of this sad state of affairs, I want to offer a model of a more productive approach. The model comes from Jewish political philosopher Michael Walzer, who I had the honor of getting to know a little bit during our years in Princeton.

Over the course of many publications and decades, Walzer developed and committed himself to a version of the social critic he called the connected critic.

The basic idea of the connected critic is quite simple. It starts with the insight that an enemy cannot be a social critic, because an enemy lacks standing. Of course our enemies will critique us, but we will never listen to them. But some argued that an ideal social critic should be neutral, or have some distance, from the society he or she was critiquing.

Walzer pushed back on that belief. He taught that the first key element of a successful social critic is that they have standing, membership he calls it, in the collective. The social critic must be part of the group they critique.

Secondly, Walzer taught, the social critic should appeal to shared values. When a society’s behavior is not living up to its own values, then the social critic can point out the gap. The form of such a critique would be: “You say you believe in this principle, but you are not following your own values!”

Walzer explored the work of many contemporary social critics, but his favorite exemplars were the Hebrew prophets. It happens that we’re reading two great examples of social critique from the prophets in our Haftarot today: one who fits the connected critic model, Isaiah, and one who does not: Jonah.

Let’s start with Isaiah. Isaiah’s famous lines, is this the fast, starving your bodies…no, this is the fast I desire: to unlock the fetters of wickedness…these verses are surrounded by detailed descriptions of the principles and values that the Israelites know they should be upholding. Isaiah says to his people: “they are eager to learn God’s ways…eager for the nearness of God…if you banish…evil speech…and offer your compassion to the hungry – then your light will shine in the darkness.” Isaiah can say all these things – that the Israelites want to be near to God and to be compassionate to the hungry because Isaiah is part of Israelite society and knows the moral teachings of the group he is critiquing. Isaiah’s critique resonates because it appeals to the best selves of the Israelites, because he is one of them.

Compare this to the afternoon Haftarah, the book of Jonah. God sends Jonah to Nineveh, a completely different mission than Isaiah’s words to the House of Jacob. Ninevites are Assyrians, not Israelites. Jonah is an Israelite prophet, and he has absolutely no standing in Nineveh. Perhaps this is why Jonah resists the mission so absolutely – why in the world would the Assyrian people of Nineveh listen to a Hebrew prophet? Jonah’s prophecy, unlike Isaiah’s, has no content. The only thing Jonah says to the people of Nineveh is “40 days and Nineveh will be overturned.” Because Jonah, Walzer argues, is not a member of Nineveh’s society, he has no idea what shared values Ninevans espouse. He can’t appeal to their higher moral values. All he can do is be a mouthpiece for God.

The lesson of these prophets is that effective social critics focus on the fate of their own community. Social critique is ultimately an act of solidarity, an act of loyalty, an act of love for the collectives we are members of.

So what would it look like to embrace the model of the connected critic in our own lives? I think it boils down to this: if you don’t consider yourself a committed MEMBER of the group you are concerned about, lower your volume, maybe even turn it off. Armchair social criticism of groups we are not connected to may be entertaining, but it is little more than noise.

But we ARE MEMBERS of collectives: our local community, our Jewish community, American society, political movements, nonprofits, school communities…For these groups, how can we be effective social critics? The basic approach is this: appeal to the group’s own values, and point out behavior that isn’t living up to those values. And then, offer to help.

It is no revelation to point out that people who chose to take on communal leadership don’t like to be criticized. But when someone comes along and reminds a leader of the group’s shared values, and points out a discrepancy, it makes it much easier for that leader to hear the critique.

I have come to see social critique as a form of collective self-correction, maybe even a form of social healing. Like a living body that sends signals when something isn’t going right – thirst, exhaustion, a fever – the social critic sends signals to the collective when all is not well.

Rabbi Yosi ben Chanina taught:[4] “A love without reproof is no love.” Social critique is ultimately an act of solidarity, loyalty and love.

James Baldwin put it this way:[5] I love America more than any other country in the world. And exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.

But Rabbi David Hartman had, perhaps, the best line. He used to say: critique me like my mother, not like my mother-in-law.

When Rabbi Stephen Wise met with the trustees of Emanu-El to interview for the senior rabbi position, he modeled what it means to be a connected critic. Instead of spouting a list of complicated social issues he could not control, he presented instead a list of concerning behaviors by people he was connected to, and, I’d like to think, people he loved.

The next time you find yourself fed up with someone or some issue, see if you can employ the model of the connected critic for good use.

[1] BT Shabbat 119b

[2] Lamentations 1:6

[3] Sifra 89a-89b

[4] Bereshit Rabbah 54:3

[5] 1955, Notes of a Native Son

Video Archive

Livestreams and an archive of all Shomrei videos is available on our YouTube Channel at shomrei.org/video